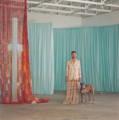

Morné Visagie is a South African artist, printmaker and curator who lives and works in Cape Town. He is represented by WHATIFTHEWORLD Gallery, South Africa, and NUWELAND Gallery, The Netherlands.

Growing up on Robben Island towards the end of Apartheid South Africa, the Atlantic Ocean that separated Visagie from the Mainland became a recurring metaphor in his imagination, and for the past decade, the colour blue has been the primary medium in his work; a personal symbol of death, loss, nostalgia, memory, religion, sexuality, exile and distance.

Morné is Krone Vintage-Only MCC’s first artist in residence, in association with WHATIFTHEWORLD. Morné’s master exhibition The Last Colour to Fade, was hosted by Krone and WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery at Twee Jonge Gezellen in Tulbagh.

In The Last Colour to Fade Morné moves with deft fluidity between personal recollections and collective history. He pairs his childhood island, its physical and psychological landscapes, with reflections on art, literature and film, drawing on the work of Damon Galgut, Derek Jarman, Jean Genet, Virginia Woolf and others in a poetic engagement with the sea and its symbols. The Last Colour to Fade – a collection of twelve discrete works – marks an abstracted expression of Visagie’s themes.